Across most of the United States, February is a boring month for birders. We’ve been stuck with the same species all winter, with no hope of reinforcements in the form of migrants until the end of March. As I wait for spring, and it’s associated turnover of species I decided to do a bit of housekeeping of my birding life list.

I’ve mentioned this before, but eBird is an absolutely amazing website for birders. It’s great for finding places to look for birds, checking recent submissions for any nearby rare or unusual birds, and linking to pictures and descriptions to help with identification. But most of all, eBird amazing at keeping lists. Listing birds is like other collecting hobby, in that more is better, complete sets or rarities are particularly fun, and conversations about which ones you have is extremely tedious to anyone who doesn’t collect. I think the difference between baseball cards or coins and birds, though, is that each item on my life list has at least one amazing memory attached to it. I’ll occasionally peruse my list and reflect on the time I saw a Great Grey Owl hunting voles in the evening light or watched a Great Curassow stride through Mayan Ruins.

Since I began using eBird in 2013, I’ve encountered (seen or heard) and logged 976 species of birds globally, 601 in the United States, and 412 in California. The problem is that I’ve seen some birds before 2013 and not since. I know for sure I’ve actually met 612 kinds in the US and 419 in California. A few of these “extra” birds are quite rare in the region, and I’ll be unlikely to ever see them there again. Therefore, in order to preserve my memories, I keep an excel spreadsheet with my USA and CA life lists. It’s easy to do in theory, but in practice, my “count” keeps changing!

Other than seeing new birds, the numbers on my list can change for two reasons. One is taxonomic change—lumping and splitting species. Based on the most recent literature, sometimes two or more species are grouped into just one. A recent example is that Common and Hoary Redpolls were found to freely interbreed, and therefore lumped into “Redpoll”. More frequently, what was formerly considered geographic variation within a species is deemed enough to elevate populations into to two or more separate species. For instance, last year Cory’s and Scopoli’s Shearwaters were split, and, as I had seen both, I got to add one to my count—an armchair tick! Numbers can also change based on which non-native species are considered “countable”. The American Birding Association (ABA, aka the birding police) keeps track of wild, but introduced populations of birds in the US and Canada, determining when they are “naturalized”—that is self-sustaining through reproduction in the wild—and thus countable. The chicken you watched crossing the road after escaping its coop doesn’t count, but the European Starling at your backyard feeder definitely does. The flock of Egyptian Geese that Jenny and I saw along the Colorado River in Austin last week? The ABA needs to make a ruling (it’s on my list, but it’s technically still a provisional species!). Finally, adding to the confusion are name changes and taxonomic revisions that alter the order birds appear of the list.

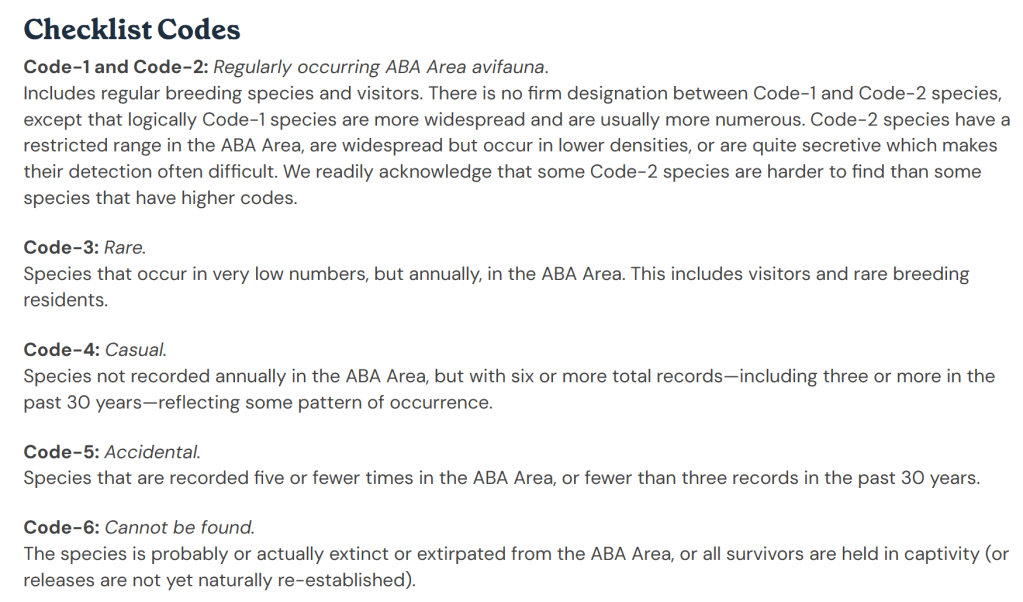

All this to say, a couple days ago I redownloaded the most recent ABA checklist, and spend a couple hours updating my excel sheet. I made adjustments to the taxonomy and additionally added the ABA rarity codes to my list. Here’s how those work:

There are 1109 species of extant (not-extinct or locally extirpated) bird species that can be counted the US, of which I’ve only seen 55%. However, 362 of those are rarities—codes 3, 4, or 5. Of those, I’ve only seen 19 (5%, including my one code 5 lifer, a White-chinned Petrel that hung out with me on a boat trip in Monterey Bay). I’ve seen about 45% of the 257 code 2 birds. Many of my code two misses would either require trips to Alaska, Hawaii, or South Texas (places I’ve never been), or are naturalized species locally found in cities (places I don’t particularly enjoy birding). That leaves the 489 code 1 birds. Of those, I’m only missing 15 (3%)! Those elusive few make a great list to search for on future adventures! Hopefully I can find a few more lifers once winter turns to spring.