Today I headed to Carvers Creek State Park for some early spring naturalizing. The park, north of Fayetteville, preserves some pristine longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) woodlands. This beautiful and diverse habitat, threatened by habitat development and fire suppression, is fast becoming one of my favorites in the state.

Normally when I’m in nature, I’m on my phone a lot. I keep a running eBird list, and have a trail map downloaded, which I check frequently. Additionally, if I have service (most places these days) I’ll take pictures of unknown lifeforms and upload them to iNaturalist, using the algorithm to generate a tentative identification. This time I wanted to try naturalizing completely offline. I printed out the map, packed a couple field guides, and hit the trail.

Amazingly, the very first bird I saw upon exiting the car, was a rare Red-Cockaded Woodpecker (Dryobates borealis). An obligate dweller of frequently burned pine-forests, this was only the third time I had ever seen one! I instinctively reached for my phone to start an eBird checklist before I remembered my brief. Instead, I opened my notebook, wrote down the four-letter of birding code RCWO and put a small dot next to it. Before everyone had an electronic recording device in their pocket, ornithologists developed a shorthand for recording their lists. Each bird has a unique 4-letter code that’s some combination of the first letters of words in the English species name. Additionally, rather than tick marks, birders often use the dot and line tally method, where you build boxes that eventually total ten individuals. This method is easier to read and harder to miscount. By the end of the day, I had a hand-written list of 28 birds and their counts. I must say, I think my totals were more accurate than my normal eBird accounting.

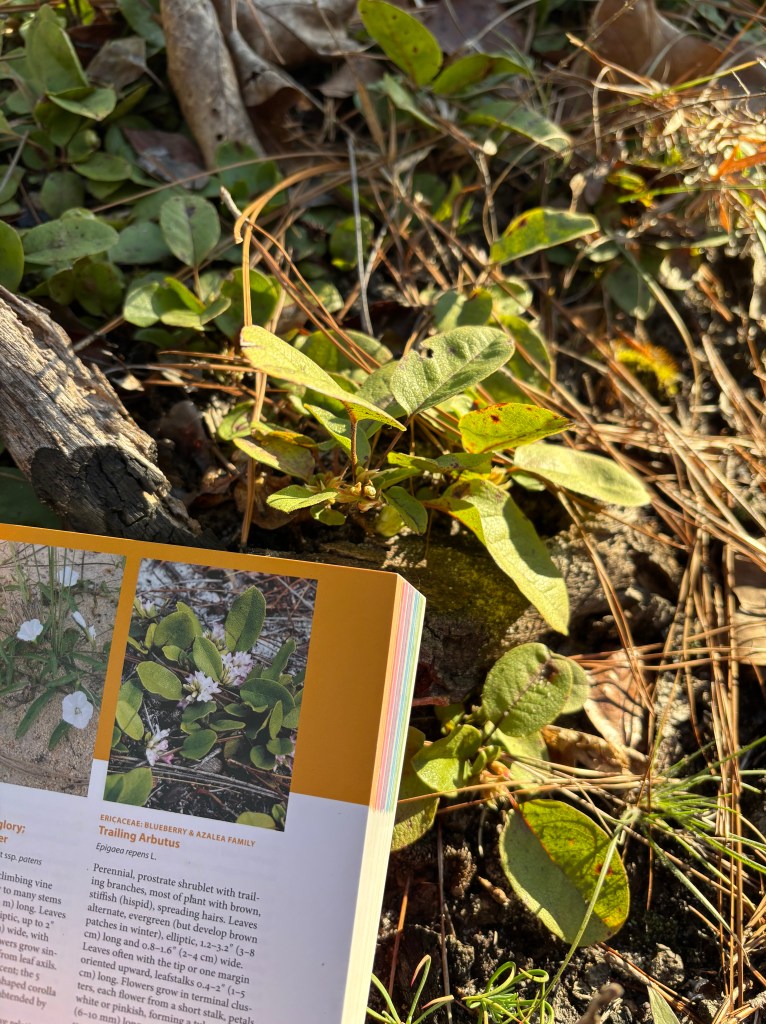

A few minutes down the trail from the woodpecker, I found a low-growing plant with lovely, fuzzy-centered white flowers.

I brought my copy of Wildflowers of the Sandhills Region by Bruce A. Sorrie for just this moment. Flipping to the appropriate section, I quickly identified it as Trailing Arbutus (Epigaea repens).

The description in the book mentioned a nice fragrance, so I lowered my nose to ground level to get a whiff. What a treat! They had a lovely smell of a less-cloying jasmine. Here was definitely a win for field-guide usage—I never would have thought to sniff if I had just used iNaturalist.

The only other plant blooming this early was my main target of the whole trip, the sandhills pixiemoss (Pyxidanthera brevifolia). Only found in six Carolina counties, this is one of the rarest plants in the region. It’s an absolutely adorable cushion-plant, densely covered with delicate flowers.

Even here, in excellent habitat, it is uncommon—I only saw one plant across eight miles of trail! I used the description in field guide to make sure I wasn’t confusing it the only other species in the genus. Using a hand lens, I saw hairs covering the leaves, which among other traits, clinched the ID.

In addition to the birds and flowers, I had an excellent day for herps, totaling nine species (no snakes though). While flipping some small logs around the edge of a pond, I found this tiny salamander!

Based on shape, I knew it was in the genus Eurycea (amazingly it’s a congener of the cave salamander I had just seen in Texas!). But I had no idea which one. Time to turn to my other old school resource—the Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Comparing the species that could be found in the area, I locked in on a couple important characteristics. Four (not five) toes on the back legs.

A yellow belly with an even paler throat and chin (compared to a darker gray).

I had just found the uncommon and recently described Chamerlain’s Dwarf Salamander (Eurycea chamberlaini)!

Other herp highlights included this chonky mud salamander (Pseudotriton montanus),

and this stunning spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata).

No field guides were needed for either of these two (In case you’re curious, I swear this is the front end of the turtle—their head is tucked is tucked behind those weird orange and black neck folds!).

Overall, I did enjoy eschewing my phone. Hiking with a notebook in my pocket encouraged me to jot down observations as I walked. For instance, based on my notes, I could figure out that a butterfly I saw flutter by was a sleepy orange (Abaeis nicippe). However, I found it somewhat annoying to transcribe my bird list when I returned. Additionally, it seems unnecessarily handicapping to not use the identification algorithms of iNaturalist when I have a perfectly good photograph and the internet. On my next hike, I’ll definitely keep that notebook in my pocket and take the time to use a field guide, if I brought the right one. But I will go back to my phone-y ways.